Manyfold

Roughly speaking, the set of all 3D modeling tools can be divided into three catagories:

- A single, simple paradigm

- All of the paradigms at the same time

- All of the paradigms at the same time (corporate yearly license edition)

Of course, this multifacetedness does come at a cost. The learning curve for these programs is primarily dominated

by the accumulation of knowledge about what features there are, as opposed to learning how to most effectively utilize

one single idea (or at least a very small set of ideas). Many larger industry standard tools in most fields 'suffer' from this.

I put 'suffer' in quotes, because, as with all things, there is a lot of nuance.

However, it would be off-topic to go into detail (I might write another post about it at some point).

For now I'll say that category 2 and 3 are not inherently bad, but that I don't enjoy using tools of that nature.

An idea

I've been thinking for a while about what would make sense as the simplest and most powerful paradigm for designing non-artistic solids.

There are existing options, but to me, it seemed that none of them were fully useful in isolation. In particular, I've been

looking for something that would allow arbitrary freeform curves and surfaces in 3D space to be straighforward to create.

NURBs come close, but are not quite it,

as they are not arbitrary (they are B-splines).

By approximation, Autodesk Fusion (even though it is a category 2-3 program in practice) is vaguely based around extruding, sweeping, and rotating sketches (which are 2D parametric constraint-based vector drawings). However, I couldn't quite put my finger on a solid and robust way to implement that in a way that remained pure.

Finally, when I saw Easymetric (in development by Oroshibu), I got a more tangible idea of what I wanted to have, even though it was not at all like that tool.

What I made

Manyfold is a 3D modeling engine library, which means that it can be used to write a program that generates a 3D mesh. The user describes the model according to Manyfold's paradigm, and Manyfold triangulates it.It can export to

.ply, .stl and .obj.

Manyfold's paradigm allows it to guarantee a volume is 'closed'. In this context, that means that, unless you tell it otherwise, it will not export any object with 2D (or 1D) features. In less formal terms, objects that you can 3D print with infill.

Currently, Manyfold is nothing more than a module for the programming language Jai (which is in closed beta). I have hopes of making a proper GUI tool around it, but 3D modeling GUIs are inherently very complicated, and I do not see a good way forward for it at the moment.

The Paradigm

The name 'Manyfold' is a play on the mathematical concept of the manifold. Manifolds can (in very loose terms) be described as maps between spaces. For our purposes, the most important example is a surface. A position on a surface can be defined with 2 numbers (surfaces are 2D), but the surface itself can exist in any higher number of dimensions, in our case, 3.

In Manyfold, the user defines surfaces, and then specifies how the boundaries of those surfaces connect to eachother. To do this, the user has to define the ranges of the u and v coordinates, and denote if the starts and end are inclusive or exclusive. When triangulating, an exclusive edge is connected to an inclusive edge of another (or the same) surface. Next to this, a range can have poles. When an edge is a pole, all points on that edge coincide, so only one point is calculated.

An example

The sphere has all Manyfold features, in the least amount of code.

#import "manyfold";

#import "Math";

main :: () {

sphere := Surface.{

name = "sphere",

u_domain = Range.{

0, 2*PI, 50, .EXCL_END

},

v_domain = Range.{

0, PI, 50, .DIPOLE

},

equation = (uv: avec2) -> avec3 { return .{cos(uv.x)*sin(uv.y), sin(uv.x)*sin(uv.y), cos(uv.y)}; },

};

sphere.u_begin_attach = Surface_Attachment.{.U_END, *sphere, false};

sphere.u_end_attach = Surface_Attachment.{.U_BEGIN, *sphere, false};

file_from_surface(*sphere, format = .OBJ);

}

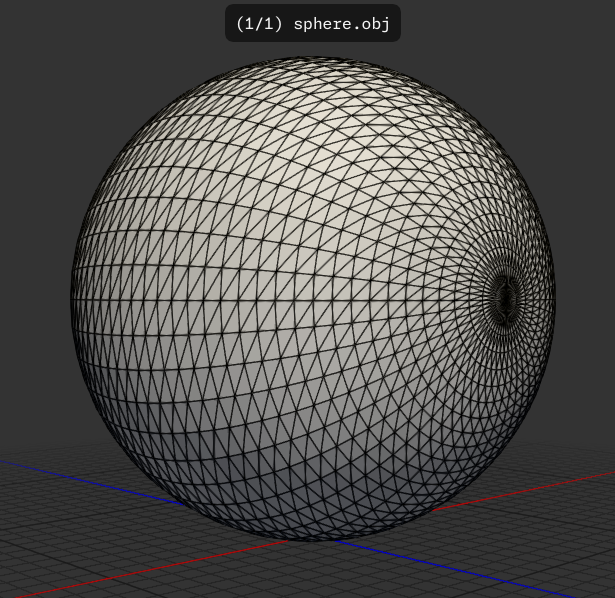

sphere.obj file (result pictured). Note that there are no primitives in Manyfold, so the equation for the sphere had to be provided.

The Range struct has 4 fields. A begin, end, resolution and kind.

The 'begin' and 'end' simply give the beginning and end values of the range. They are allowed to be ascending and descending, though this will influence the winding order of the triangles on the surface.

'resolution' is an integer that tells the module how many subdivisions should be made during triangulation.

Finally, 'kind' denotes whether the begin and end are inclusive, exclusive, or poles.

We can see that the u domain goes from 0 to Tau in 50 increments, and that its end is exclusive. Its begin is inclusive, which is the default.

The v domain goes from 0 to Pi, also in 50 increments, and has poles on both ends. These are inclusive as well.

equation is the parametric equation for a unit sphere at the origin (where u is phi and v is theta).

After the main definition, we encounter two lines that seperately modify two fields. They are on seperate lines because referencing a pointer to a variable during the definition of that variable is not allowed in Jai. These lines define how the u domain's edges are attached to other edges. In this case, the beginning and the end of u are attached to each other, because a sphere is a fully closed surface. The v domain does not need to have attachment definitions, because its inclusive poles are already fully closed.

The Surface_Attachment struct that defines these attachments has 3 fields:

kind, which is an enum that references which other edge to attach to,

surface, a pointer to the surface where to look to attach,

and reversed, a boolean that says to stitch the two edges in opposing directions, which is sometimes nessecary to prevent all sorts of strange overlapping.

Problems and limitations

The paradigm can describe any volume (of any genus). However, it cannot guarantee that surfaces do not intersect. Sadly, verifying if and exactly where a completely arbitrary surface intersects with itself or another surface is actually technically impossible. Of course, the problem can be constrained to become a lot more manageable, but more on that later.

Even though it can describe any volume of any genus, that does not mean it is convenient to do so. Something as basic as a cube has 6 surfaces (already a lot of paperwork). Adding features to any of the surfaces usually means that that surface now has to consist of several surfaces. This is a problem, because any surface's edge can only connect to one other edge, and so when one surface has been turned into multiple, all of the connecting surfaces usually also need to be divided, unless you get really clever with it.

Something else that often happens, is that the final shape ends up being simple linear interpolation between a couple of curves in 3D space. This is not inherently a problem, but it's informative about whether or not this paradigm is solving the correct problem.

Somewhat in conclusion, the Manyfold paradigm solves 1 problem somewhat well: Volumes that consist purely of a low number of surfaces with arbitrary compound curvature, connected to eachother in straightforward ways.

What's next?

Manyfold is not the ultimate solution. Both constraint-based sketching and boolean volume modification are still more practical paradigms for creating useful shapes (though neither solve the problem that Manyfold does).

The central feature that Manyfold misses out on is intersection between surfaces. Boundaries of surfaces are only defined by the limits of the uv-coordinates, but in most cases this is not generally useful. As hinted at earlier, analytical surface intersection detection/solving is technically impossible, but that is really only because the surfaces in question are arbitrary. To 'solve' this, there are at least 3 possible ways forward:

- Only do intersection detection at the mesh stage.

- Only allow intersection detection for known shapes.

- Allow intersection detection to have reasonable margins of error (lower margins cost more compute).

Finally, it must be mentioned that making any sort of shape is inherently a very graphical process. GUI must eventually exist for it, and the paradigm should allow for that.